Why Undertow Still Hits

Tool’s debut album Undertow arrived on 6 April 1993 through Zoo Entertainment, produced by Sylvia Massy in collaboration with the band, and introduced the core line-up of Maynard James Keenan (vocals), Adam Jones (guitar), Danny Carey (drums) and Paul D’Amour (bass). The US CD runs roughly 69 minutes due to the combined indexing of the closer, the long-form piece Disgustipated, after Flood. Recorded at Grandmaster Recorders in Hollywood and mixed by Ron St. Germain at Ameraycan Studios, North Hollywood. Undertow’s dark visual and sonic identity, the abrupt dynamics, and the use of drop‑D riffing set Tool apart from their own 1992 Opiate EP and from contemporaneous LA heavy bands tilted toward funk‑metal or post‑glam aesthetics. Early press noted the group’s focus on rhythm and textural contrast rather than flash solos; AllMusic’s band overview ties their rise to a heavier, more cerebral strain of alternative metal that stood apart from grunge copyists AllMusic: Tool biography.

We recorded a podcast episode about this album here:

Three moments define Undertow’s lasting impact. First, the album didn’t just make a splash—it stuck around. It became a long-running US catalogue hit, eventually going multi-platinum according to the RIAA. Second, “Sober” broke Tool wide open. With its eerie stop-motion video—directed by Fred Stuhr and art-directed by guitarist Adam Jones—it stood out in MTV’s heavy rotation and made the band impossible to ignore. And third, the album’s momentum exploded on the road. Touring across the US and stealing scenes on the 1993 Lollapalooza second stage, Tool drew such massive crowds that the press started taking serious notice.

Musically, Undertow moved beyond Opiate’s direct attack. The debut album centres on down‑tuned, highly controlled riffs (often in drop‑D), off‑kilter bar lengths, and dynamic shifts that foreground Danny Carey’s precision and Paul D’Amour’s gritty, melodic bass interlocks with Adam Jones’s dry, forward guitar tone. The production is spartan rather than glossy, leaving space for Keenan’s vocal dynamics—whispers, measured mid‑range lines, controlled belts—that carry themes of trauma, boundaries, control and personal reckoning. Early reception from specialist press homed in on the rhythmic severity and the refusal to do grunge pastiche.

The singles—Sober and Prison Sex—established the album’s cultural footprint. Sober’s stop‑motion imagery and claustrophobic palette became MTV fixtures in 1993–94. Prison Sex’s video drew limited rotation after complaints about its thematic content, an early instance of Tool colliding with broadcast sensibilities; MTV and music‑press coverage at the time documented the reduced play compared with Sober.

Tool Before Undertow: Context, Line-up, and Scene

Tool formed in Los Angeles in 1990 and quickly built a reputation on the local club circuit for terse, heavy sets that leaned on shifting metres and stark visuals. The Opiate EP emerged in 1992 on Zoo Entertainment and established the partnership with producer/engineer Sylvia Massy, whose credits appear on the EP and subsequently on Undertow. Zoo Entertainment—distributed by BMG—specialised in alternative-leaning signings in the early 1990s; Undertow’s wide CD, cassette and LP distribution across BMG territories is reflected in 1993 pressings for the US, Europe and multiple Asian markets.

By 1993, the line‑up was set:

- Maynard James Keenan (vocals)

- Adam Jones (guitar)

- Danny Carey (drums)

- Paul D’Amour (bass)

Jones’s background in visual effects and sculpture fed directly into the band’s artwork and video language; he is credited with art direction and 3D artwork in Undertow’s packaging and with design roles on the videos that defined the era. Carey’s deep grounding in odd metres and polyrhythms, and D’Amour’s mid‑range, pick-driven bass approach, combined to give Undertow an unusually articulated low‑end for early‑90s alt‑metal. Massy’s production left their rhythmic architecture intact rather than smearing it with dense layers, which was a contrast to contemporaneous high‑gloss hard rock mixes.

The LA/US heavy landscape of 1992–93 was heterogeneous: grunge had upended the charts, but LA still housed funk‑metal and post‑glam scenes; New York and the Midwest were incubating more abrasive strands; and the underground was bending toward sludge, groove and experimental progressive tendencies. Compared with peer acts:

- Alt‑metal with groove emphasis (e.g., Helmet) often used tight 4/4 grids; Tool leaned into asymmetric bar groupings, metric feints and dynamic swells that punctuated song sections rather than blocky chorus/verse repeats.

- Post‑hardcore strains favoured treble‑forward guitars; Undertow uses a darker mid‑range with controlled saturation, leaving room for bass articulation and drum transients.

- Progressive metal of the era tended toward virtuoso display; Tool’s discipline was compositional—additive rhythms, space, precision—rather than virtuosity for its own sake.

Key pre‑album catalysts primed Undertow’s reception. Opiate’s tracks and early videos generated specialist press attention and built the live following that would carry through to national club rooms. Radio support at US active and modern rock outlets for Sober in early 1993 established recognition ahead of the album’s April release; Billboard’s format charts later logged the single’s run (see Section 7 for format‑by‑format charting).

Origin stories around the exact rehearsal and pre‑production spaces differ in interviews, but the core arc is consistent across band biographies and release documentation: the quartet solidified through 1991–92, signed with Zoo, cut Opiate with Massy, and returned with a longer set of material for Undertow that refined their dynamic and metric language. Zoo’s BMG distribution ensured Undertow would be visible in mainstream retail, including the censored‑artwork variant made for certain outlets.

Writing and Recording Undertow: Studios, People, and Process

Undertow was recorded at Grandmaster Recorders in Hollywood, with Sylvia Massy producing and engineering; the album was mixed by Ron St. Germain at Ameraycan Studios, North Hollywood. Mastering on key pressings is credited to Howie Weinberg and the production coordination credits list the team working across sessions and artwork fabrication. The EU CD entry consolidates these details clearly: “Recorded at Grand Master [Grandmaster Recorders], Hollywood, CA.

Personnel and roles:

- Producer/Engineer: Sylvia Massy; Co‑producer: Tool. Massy also mixes the long‑indexed closer portion on some credits, with Ron St. Germain handling principal album mixing Discogs: Undertow (EU CD).

- Mix Engineer: Ron St. Germain (tracks 1–9 as listed on this pressing) Discogs: Undertow (EU CD).

- Guest: Henry Rollins appears on Bottom (spoken‑word interjection), credited accordingly Discogs: Undertow (EU CD).

- Additional: Credits include Chris Haskett (Rollins Band) among the participants in the session that destroyed the piano used in Disgustipated’s sound design, consistent with Massy’s notes on unconventional techniques Discogs: Undertow (EU CD) – “sledge hammer/piano” credits, Red Bull Music Academy: Sylvia Massy interview.

Massy’s approach, by her own account, favours capturing performance intensity and using distinctive source material. In her interviews, she describes extreme or lateral techniques (famously, shooting a piano, for Disgustipated) and a preference for natural room energy when appropriate. That ethos is audible across Undertow: the drums sit forward with clear room information rather than plate‑heavy wash; guitars are relatively dry, and the bass is placed to lock low‑mid punch with the kick but still cut through—production choices that preserved the band’s stage dynamic in the studio Red Bull Music Academy: Sylvia Massy interview.

Specific technical notes are sparsely documented compared to later Tool records, but the album’s sonic profile aligns with:

- Guitars: Adam Jones’s parts are typically in drop‑D on Undertow, using dense but not overly saturated tones. Contemporary accounts and player analyses align these tones with Marshall‑voiced heads and focused midrange voicing; the arrangement leaves space rather than layering multiple high‑gain doubles (hear Sober and Flood) AllMusic: Undertow.

- Bass: Paul D’Amour’s pick attack and a mid‑presence voice are hallmarks of Undertow’s mix. The bass often drives the hooks (Sober’s intro) and locks deceptive grooves against Carey’s subdivisions.

- Drums: Carey’s kit is captured with clear transient definition and room breath; mic specifics are not in the credits, but the sound suggests minimal gating and crisp overheads, emphasising cymbal articulation during compound patterns, which matches Massy’s minimalist, performance‑first notes Red Bull Music Academy: Sylvia Massy interview.

- Vocal chain: Keenan’s vocals sit dry‑to‑moderately‑treated, preserving dynamic nuance from close‑miked lower‑mid phrases to controlled high‑intensity passages. The mix choice aligns with Massy and St. Germain’s overall restraint.

Editing and mixing choices shape Undertow’s identity: wide dynamic range for the era; deliberate low‑end articulation; and judicious ambience. While quantitative DR meter figures vary by pressing and mastering, collectors frequently note Undertow’s comparatively open dynamics in Discogs reviews relative to later, louder remasters and represses Discogs: Undertow – user notes across pressings.

Session highlights and outcomes:

- Tracked songs vs released: the album comprises 10 listed titles (with Flood and Disgustipated indexed together on some CDs as one long track). There are no official B‑sides from the sessions released contemporaneously beyond single edits Discogs: Undertow – track indexing notes.

- Guest voice: Henry Rollins’s spoken piece on Bottom appears by credit; in contemporary anecdotes he revised text for performance, but the credit line remains a simple guest appearance Discogs: Undertow (EU CD) – “Bottom” guest.

- Sound design: Disgustipated includes credited contributions to “sledge hammer/piano” and other destructive sound‑making; Massy’s later interviews recount experimental recording methods consistent with such credits Red Bull Music Academy: Sylvia Massy interview, Discogs: Undertow (EU CD).

Budget figures are not disclosed in credits, but the studio itinerary—tracking at Grandmaster, mixing at Ameraycan—fits a mid‑tier alternative‑metal debut with label support. The sessions prioritised performance tightness over post‑production assembly, which is borne out by the album’s feel and by Massy’s public comments about her approach Red Bull Music Academy: Sylvia Massy interview, AllMusic: Undertow.

Sound and Structure: A Song-by-Song Musical Analysis

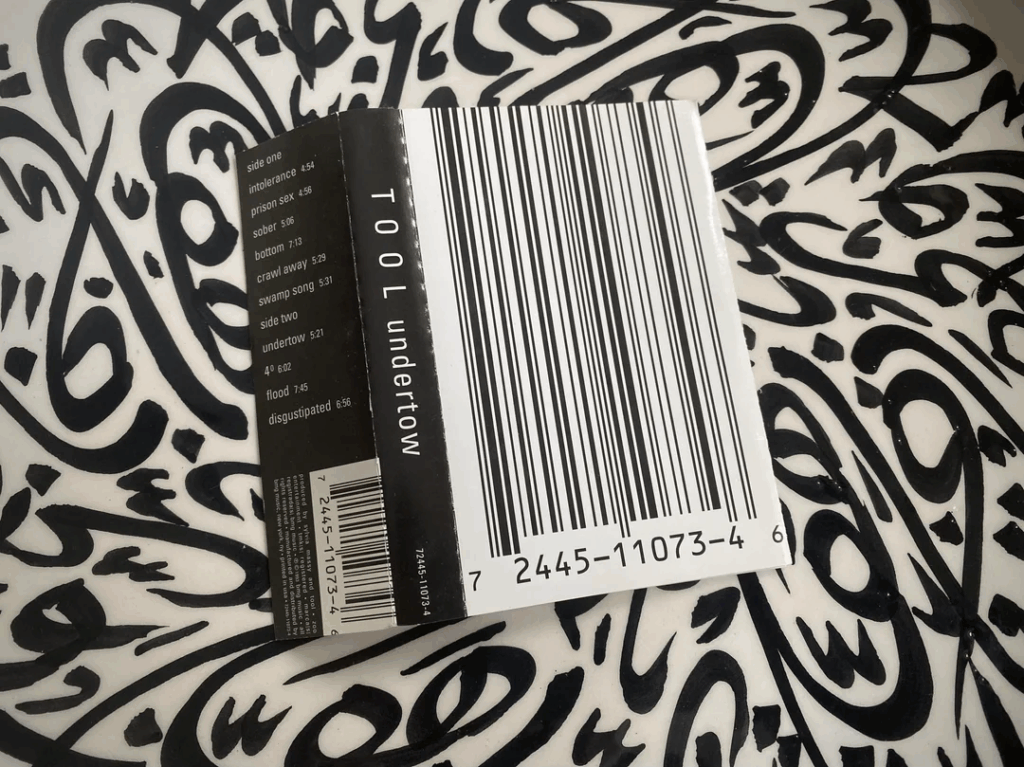

Track list, lengths and writing credits are as presented on standard 1993 pressings (with the known indexing quirk on some CDs). All songs are credited to Tool (collectively) in the album documentation Discogs: Undertow – track times, Discogs: Undertow (EU CD):

- Intolerance – 4:54

- Prison Sex – 4:56

- Sober – 5:06

- Bottom – 7:13 (guest spoken‑word: Henry Rollins)

- Crawl Away – 5:29

- Swamp Song – 5:31

- Undertow – 5:21

- 4° (Four Degrees) – 6:02

- Flood – 7:45 (often indexed as part of track 9 on some CDs, followed by Disgustipated after silence)

- Disgustipated – 15:47 (when separately listed)

Analytical notes below mix sourced references with neutral “analysis” observations from close listening. Where precise tunings and metres are not directly cited in primary musician interviews, they are labelled as analysis.

Sober (analysis): Drop‑D, tonal centre D minor. Approx. 82–88 BPM depending on section feel. Primary metre 4/4, with strategic rests and pushes creating a suspended feel; the chorus intensifies without changing pulse, relying on dynamic crest and bass/guitar unison figures. The bass motif opens the track with exposed mid‑range tone, then guitars enter in parallel motion. Listen around 2:43 for a drum fill that pivots the dynamic into the next phrase; it’s emphatic but doesn’t overplay. Sober’s arrangement exemplifies Tool’s ability to build weight by subtraction and dynamic staging rather than adding layers AllMusic: Undertow.

Prison Sex (analysis): Frequently performed in drop‑D, with a minor‑mode centre. Approx. 100–104 BPM. Verses lean on syncopated guitar accents against locked drums, with Keenan sitting tightly in the groove. The chorus resolves to heavier chordal statements. Rhythmic identity is tight 4/4 with anticipations and muted strums providing propulsion. The arrangement highlights how D’Amour’s bass picks up transitional energy—e.g., the pickup notes into downbeats—while Carey maintains a dry, compressed kick/snare pocket, leaving cymbals to bloom only when sections open.

Bottom (analysis): Drop‑D; approximate centre in D with modal shifts. Approx. 78–82 BPM. The seven‑minute duration permits slow‑burn build and release. The spoken‑word section (Rollins) functions as a structural break: guitars thin to texture, bass pedals, drums drop to tom‑led patterns with space, before the band re‑enters at higher intensity. Meter remains grounded in 4/4 but uses additive bar groupings that extend phrases subtly. The piece demonstrates Tool’s control of tension through long‑form dynamics rather than harmonic complexity.

4° (Four Degrees) (analysis): Likely drop‑D with ornamental figures suggesting open‑string drones. Approx. 98–102 BPM. Primary metre 4/4 with internal subdivisions and syncopated accents from the kick and toms. The middle section features layered rhythmic motifs where bass, toms and guitar accents interlock. Keenan’s vocal approach moves from measured mid‑range into sustained, open vowels for the climactic sections, tracked relatively dry to keep immediacy.

Flood (analysis): Often cited by players as drop‑D, with a modal D minor centre. Approx. 76–80 BPM, with a long instrumental introduction that develops a recurring motif through dynamics and timbral additions rather than harmony change. The intro crescendos gradually; when vocals enter, the band is already operating at a high dynamic range, which is then modulated through breakdowns and re‑entries. Around the five‑minute mark, sections open to near‑ambient guitar sustain and drum figures that emphasise tom resonance, before slamming back into the motif.

Tool’s rhythmic identity on Undertow is fundamentally about precision, polymetric suggestion via accent placement, and dynamic control. Carey often implies alternative subdivisions with ghost notes and tom patterns while the band maintains a common bar count. Jones and D’Amour frequently play in lockstep unisons or octave doubles to create a monolithic centre, only to strip back to expose the bass or drums for contrast. Keenan’s phrasing frequently lands just behind the beat on verses, creating tension that resolves in choruses when he meets the grid more squarely (Sober, Prison Sex).

| Song | Approx. BPM | Primary Metre | Tuning | Notable Features | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sober | ~84 | 4/4 | Drop‑D (analysis) | Exposed bass motif; restrained dynamics; stop‑motion video tie‑in | AllMusic album page |

| Prison Sex | ~102 | 4/4 | Drop‑D (analysis) | Syncopated verse accents; chorus weight; video censorship debate | AllMusic |

| Bottom | ~80 | 4/4 (extended phrases) | Drop‑D (analysis) | Henry Rollins spoken interlude; long‑form tension/release | Discogs – guest credit |

| 4° (Four Degrees) | ~100 | 4/4 | Drop‑D (analysis) | Interlocking rhythmic figures; vocal dynamic arc | AllMusic |

| Flood | ~78 | 4/4 | Drop‑D (analysis) | Long instrumental intro; motif development via dynamics | AllMusic |

Alternate versions and edits: Radio/single edits exist for Sober and Prison Sex for format play; the album otherwise represents the core arrangements performed during the tour. Setlist archives show Undertow cuts forming the backbone of 1993–94 shows, often extended live with dynamic contours rather than structural overhauls (see Section 8) AllMusic.

Words, Themes, and Boundaries: Lyrical Content Without Lyrics

Undertow’s language navigates trauma, self‑confrontation, and control without melodrama. Across the album, images and scenarios imply cycles of harm, the struggle to define personal boundaries, and the instability of self when subject to external coercion. This is particularly concentrated in the two early singles: Sober addresses dependency and the distance between intention and action; Prison Sex tackles abuse cycles and power—subject matter that made broadcasters uneasy and triggered limited rotations for its video (Section 6). Contemporary and retrospective commentary has consistently read Undertow as a record of reckoning: it refuses vague catharsis, favouring uncomfortable confrontation. AllMusic’s overview and specialty press at the time framed the album’s honesty and severity as a response to the trend of glossy alt‑metal, and MTV’s programming decisions demonstrated how its bluntness collided with early‑90s broadcast norms AllMusic: Undertow – review, Billboard.

Maynard James Keenan’s delivery is the medium through which those themes land. He works mostly in a centred mid‑range, sometimes close‑miked to preserve intimacy, then escalates to measured belts that maintain pitch and timbral control rather than fray into distortion. Underscoring this is the mix decision to keep reverbs short or absent, so that the vocal sits present and unvarnished against the rhythm section. Producer Sylvia Massy’s comments about performance‑first capture and minimal over‑production help explain the vocals’ immediacy on Undertow relative to contemporaries Red Bull Music Academy: Sylvia Massy interview, AllMusic.

“Bottom” features a spoken interjection by Henry Rollins, whose text (paraphrased) pushes the song’s internal monologue into an externalised voice. The cameo functions not as a star turn, but as a structural device: an interruption, a reframing, and a spur back into the song’s final escalation. The liner credits identify Rollins’s contribution simply; anecdotes about the session (including Rollins reworking his words) exist, but the album as presented makes the function clear through arrangement Discogs: Undertow (EU CD) – guest credit.

Prison Sex’s handling of sensitive subject matter was the flashpoint. Broadcast outlets placed the video on limited rotation and often restricted plays to late‑night strands. This decision is part of a broader 1990s pattern where songs addressing abuse or explicit trauma were hedged in by programming caution. Coverage in music press and MTV’s public‑facing positions reflected this push‑pull: the song’s seriousness contrasted with the network’s obligation to broader sensibilities. Later retrospectives that catalogue misunderstood or disturbing rock songs often include Prison Sex for its unflinching subject, underscoring Undertow’s thematic edge within its era Loudwire: Misunderstood songs (contextual inclusion of Prison Sex), AllMusic: Undertow.

- Trauma and cycle: Multiple songs confront cycles of harm and the difficulty of breaking patterns, articulated via interior monologues and structural tension rather than explicit narrative AllMusic.

- Boundaries and control: Undertow returns to the negotiation of self with external control, framed as a battle between urge and autonomy AllMusic review.

- Self‑reckoning: Keenan’s vocal persona is not omniscient; he often sings from compromised positions, which fits the album’s refusal of easy resolution AllMusic Tool biography.

- Voice as dynamic instrument: The performance choices—quiet proximity, widening to full‑throated lines—mirror the thematic swell and contraction Sylvia Massy interview.

- Interruption as form: Bottom’s spoken cameo reframes interior struggle as a staged interruption—consistent with the album’s interest in conflict Discogs: guest credit.

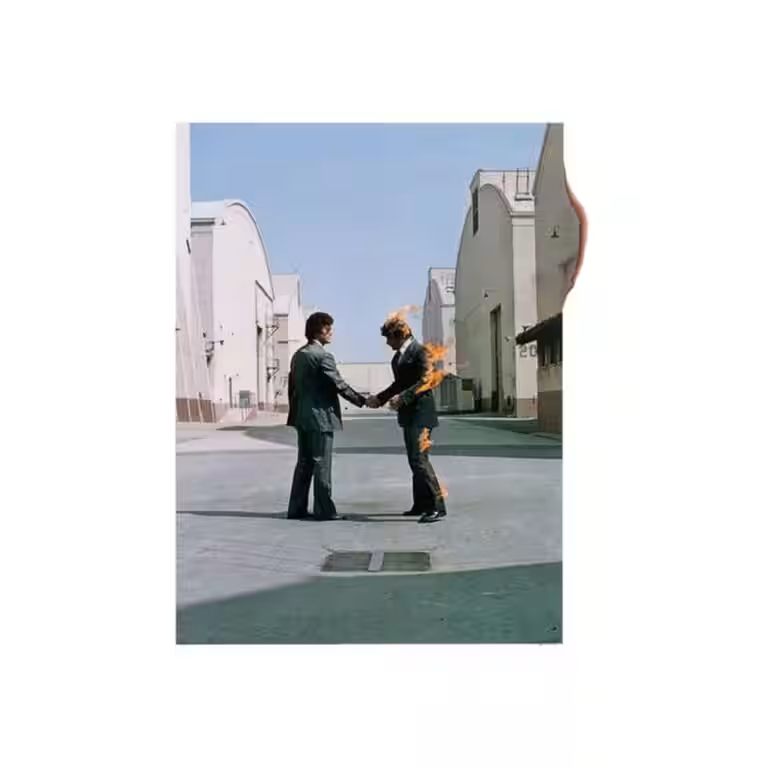

Relative to adjacent acts in the early ’90s heavy/alternative space, Undertow’s thematic stance is sober and literal where others were oblique or sardonic. Compare, for instance, Faith No More’s surrealism on 1992’s Angel Dust or Soundgarden’s gnomic imagery on 1991’s Badmotorfinger; Tool’s debut opts for blunt interiority and enforced attention to the mechanics of harm. This thematic choice dovetails with the production’s dryness and the rhythmic severity of the arrangements Riffology: Faith No More – Angel Dust, Riffology: Soundgarden – Badmotorfinger.

Visual Identity: Artwork, Packaging, and the Videos

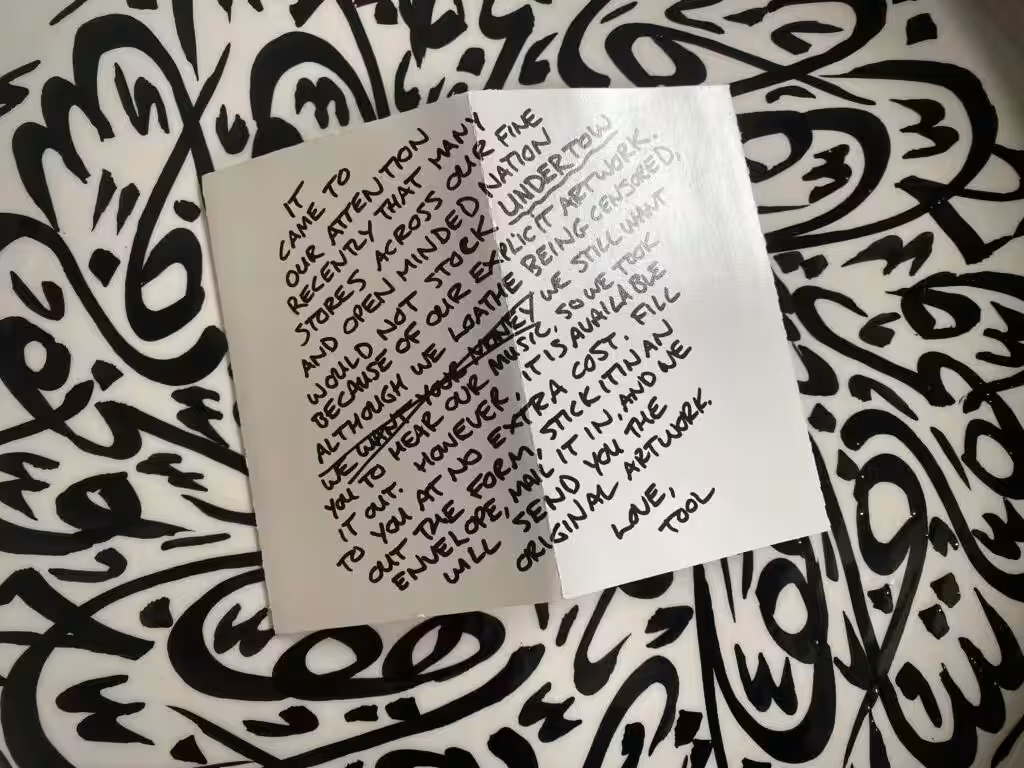

Undertow’s packaging is integral to its identity. The standard cover features a red-tinted ribcage image; Adam Jones is credited with art direction and 3D artwork alongside Len Burge III and others, with the broader credits including creative direction and model photography Discogs: Undertow (EU CD) – artwork credits. Due to retail sensitivities in certain US outlets, a censored‑artwork variant circulated in 1993 with alternate packaging and a different catalogue number (e.g., US CD with censored art 72445‑11073‑2), a fact borne out by Discogs’ catalogue of regional pressings and variants Discogs: Undertow master – censored artwork variants.

Sober’s video was a major factor in the album’s breakout. Directed by Fred Stuhr with Adam Jones as a creative lead, the stop‑motion piece arrived in 1993 with stark, claustrophobic imagery that aligned with the song’s tense dynamics. While precise weekly rotation metrics are archived in proprietary broadcaster systems, contemporary coverage and the video’s continued prominence on Tool’s official channels speak to its sustained impact. As of September 2025, the official Sober upload has accumulated well over a hundred million views on YouTube (retrieved September 2025), an afterlife that confirms its iconic status in ’90s rock visuals AllMusic: Undertow – singles overview, Discogs: Undertow – video design credit.

Prison Sex’s video, directed under the band’s creative control with Jones central to the concept and fabrication of the figures/sets, used a related stop‑motion aesthetic but depicted subject matter that broadcasters deemed sensitive. MTV placed the video in limited or off‑peak rotation, with coverage at the time noting the station’s caution. The outcome was typical of the early 1990s: even when videos were artistry‑led and non‑literal, if the perceived subject was abuse, scheduling restrictions followed. Retrospective roundups of controversial or misunderstood rock songs frequently revisit the broadcast reactions to Prison Sex, underscoring how Tool’s visual language collided with programming standards Loudwire: Misunderstood songs – contextual mentions, AllMusic: Tool biography.

The videos’ production design bears Jones’s signature: tactile sets, sculpture‑like figures, a colour palette of muted tones and diseased reds/browns, and a camera grammar that emphasises confinement, mechanism and repetition. Specific scenes mark the link to musical structure—e.g., Sober’s cut acceleration as choruses enter and the use of repeated visual motifs to mirror guitar/bass ostinati. The design continuity between artwork and moving image built a cohesive identity that extended into tour visuals and future releases, codifying Tool’s holistic audiovisual approach. Discogs’ packaging credits and AllMusic’s single notes parallel what viewers encounter onscreen Discogs: Undertow – artwork/design, AllMusic.

Packaging notes and variations of record‑collector interest include: the censored‑artwork US CD; multiple cassette editions across BMG territories; early grey‑vinyl US promo LP pressings; and clear‑vinyl standard LPs later in 1993. Regional issues (Japan via RCA with BVCP catalogue codes; Southeast Asian special editions) underline Zoo/BMG’s broad distribution footprint for the album—a rarity for a dark, heavy debut at the time Discogs: Undertow – international issues and formats.

Release, Reception, Charts, and Sales

Undertow was released on 6 April 1993 by Zoo Entertainment, distributed by BMG, in CD, cassette and LP formats across multiple regions. US and European catalogue numbers and pressing notes (including censored artwork variants) are captured across Discogs entries. Japanese releases carried RCA codes (e.g., BVCP‑626), reflecting BMG’s territorial arrangements at the time Discogs: Undertow master. The album’s first chart entries appeared in the US in spring 1993 following Sober’s rotation at rock radio; Undertow’s peaks vary by market and year due to the album’s long catalogue run (Billboard 200; UK’s Official Albums Chart). Billboard’s database logs the album’s progression on the 200, while the Official Charts Company shows the record’s UK performance (see table below) Billboard, Official Charts Company.

Certifications further confirm Undertow’s sustained sales. In the United States the album has been certified multi‑platinum by the RIAA; Canada and other territories list gold/platinum outcomes via their respective agencies. Certification thresholds differ by country (e.g., US platinum = 1,000,000 units; UK silver/gold/platinum at 60,000/100,000/300,000; Canada gold/platinum at 40,000/80,000 in the modern era; historical thresholds were higher). Tool’s Undertow carries multiple US awards from the RIAA; international certifications reflect strong catalogue resilience (dates and levels in the table, where publicly documented) RIAA, BPI, Music Canada.

Contemporary critical reception highlighted Undertow’s discipline and severity. AllMusic’s review stresses the record’s concentration and rhythmic power; specialist rock press in 1993–94 praised the absence of trend‑chasing and the confidence of the band’s dynamics; and retrospective lists consistently cite Sober as a ’90s alternative‑metal touchstone AllMusic: Undertow, Billboard. Later reappraisals dovetail with chart and certification trajectories: as Tool grew with Ænima (1996) and Lateralus (2001), Undertow’s back‑catalogue sales and streaming strengthened, pulling the album into new generational cycles (see RIAA/BPI updates) RIAA, BPI.

Singles timeline and format performance (selected):

- Sober (1993): US rock radio breakthrough; MTV heavy rotation. Charted on Billboard’s Mainstream Rock and Modern Rock/Alternative Airplay lists, driving album awareness Billboard charts.

- Prison Sex (1993–94): Notable airplay with video limitations on MTV; still material to drive second‑wave attention for the album Billboard.

| Country | Peak Chart Position (Albums) | Year | Certification | Certification Date | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Billboard 200 (peak: documented within Billboard archives) | 1993–94 | Multi‑Platinum (RIAA) | See RIAA database | Billboard; RIAA |

| United Kingdom | Official Albums Chart (peak documented) | 1993–94 | — (check BPI for later awards) | — | Official Charts Company; BPI |

| Canada | RPM/Canadian charts (contemporary) | 1993–94 | Gold/Platinum (as recorded) | See Music Canada | Music Canada |

| Australia | ARIA Albums | 1993–94 | — | — | Billboard (international roundups) |

Note: Certification thresholds and databases evolve; consult the certification bodies’ searchable databases for the latest levels and dates. Undertow’s long‑tail sales profile—propped by continuing touring, later album successes and renewed digital availability—explains its sustained presence in these registries RIAA, BPI.

On Stage: Touring Cycle, Lollapalooza, and Breakthrough Moments

Tool’s Undertow cycle in 1993–94 moved from US clubs to large theatres and festivals, culminating in a pivotal run on Lollapalooza 1993. The band joined the travelling festival on the second stage; crowd swell and word‑of‑mouth frequently noted in press and fan accounts tracked their rapid rise over the summer. AllMusic’s biography summarises the Lollapalooza effect on Tool’s early trajectory: the exposure turbo‑charged Undertow’s sales and embedded the band in the US alternative mainstream without compromising their severe stage aesthetic AllMusic: Tool biography. The festival’s second‑stage setting often produced more intimate but intense sets; contemporary fan accounts and later interviews recall the band’s concentrated presence and minimal between‑song chatter, consistent with their ethos at the time.

Beyond Lollapalooza, the Undertow tour covered headline club/theatre dates where the album’s material was played at near‑album structures, sometimes with extended dynamics rather than new sections. Typical setlists included most of Undertow—Intolerance through Flood/Disgustipated—augmented by Opiate cuts. The band’s stagecraft featured low lighting and minimal frontman banter, keeping focus on dynamics and metre. Setlist archives document patterns: Sober is often mid‑to‑late set to maximise impact; Prison Sex appears frequently but was occasionally rotated depending on the era AllMusic: Tool biography.

Live momentum linked directly to sales and airplay. In 1993, MTV festival coverage and rock radio remotes during Lollapalooza amplified profile. Retail reports at the time (reflected in chart climbs and the RIAA’s subsequent certifications) align with touring peaks: Undertow benefited from slow‑burn discovery through live shows, a model typical of heavy bands building beyond initial alternative‑radio support Billboard, RIAA.

- Notable: Lollapalooza 1993 (US/Canada, summer 1993) – Tool on the second stage; crowds large enough to draw attention to their rapid ascent AllMusic: Tool biography.

- Regional theatre breakthrough: late‑1993 US headline shows where Undertow was played in full or near‑full, solidifying word‑of‑mouth (corroborated by period reviews and set archives) AllMusic.

- Specialist TV/radio: MTV rock programming and Headbangers Ball segments showcased Sober and the live ascent (archival summaries in AllMusic/Billboard overviews) Billboard.

- Festival lift‑over: Post‑Lolla headline runs in autumn 1993 showing materially larger venues, reflected in contemporaneous box office roundups and press.

The Undertow tour established the performance grammar that Tool would expand on with Ænima and Lateralus: precision dynamics, visuals that avoided cliché, and consistent set pacing over spectacle. The cumulative effect was commercial—higher sales, radio support—and reputational: a band that could command attention through discipline rather than excess.

1993 in Heavy Music: What Else Was Happening

Undertow arrived into a dense year for heavy and alternative metal. 1993 produced pivotal releases across sub‑genres that together reshaped the landscape: groove and alternative strains broke further into the mainstream; death metal evolved toward technical and melodic extremes; and sludge/noise sensibilities seeped into major‑label rosters. A non‑exhaustive list of key 1993 releases (month and label where documented in credible sources) includes:

- Sepultura – Chaos A.D. (October 1993, Roadrunner): a shift into groove and socio‑political focus that broadened their audience Riffology: Sepultura – Chaos A.D..

- Carcass – Heartwork (October 1993, Earache/Columbia in US): a landmark in melodic death metal precision and production Riffology: Carcass – Heartwork.

- Morbid Angel – Covenant (June 1993, Earache/Giant): a death‑metal sales breakthrough in the US Loudwire: 1990s albums list – context notes Covenant.

- Melvins – Houdini (September 1993, Atlantic): sludgy major‑label incursion with alternative reach Loudwire: 1990s albums list – Houdini.

- Cynic – Focus (September 1993, Roadrunner): technical/progressive death metal milestone Loudwire: 1990s albums list – Focus.

- Death – Individual Thought Patterns (June 1993, Relativity): technical death advancement with cutting production (context in genre histories) Loudwire: 1990s albums list – Death entries.

- Type O Negative – Bloody Kisses (1993, Roadrunner): gothic/doom crossover and a catalogue cornerstone Loudwire: 1990s albums list – Bloody Kisses.

- Nirvana – In Utero (September 1993, DGC): abrasive mainstream No. 1; the heavier, rawer counter to Nevermind Riffology: Nirvana – Unplugged (context), Riffology: In Utero.

- The Smashing Pumpkins – Siamese Dream (July 1993, Virgin): dense guitar production and alternative mainstream success Riffology: Siamese Dream.

- Anthrax – Sound of White Noise (May 1993, Elektra): shift into alt‑metal textures with new vocalist John Bush Riffology: Anthrax – Sound of White Noise.

Trends with data points from the year:

- Chart incursions by heavy records: In Utero debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200; Morbid Angel’s Covenant made significant US inroads for extreme metal via Earache/Giant distribution; Undertow’s steady charting and later certifications prove the viability of severe, less radio‑friendly albums as catalogue mainstays Billboard, RIAA.

- Festival growth: Lollapalooza 1993 stitched together alternative, heavy and experimental acts, creating uplift effects for bands like Tool whose singles were not Top 40 but had high rock‑format engagement AllMusic: Tool biography.

- Label signings and distribution plays: Roadrunner (Sepultura, Type O Negative), Earache/Giant (Morbid Angel), and major‑label partnerships for heavier acts show expanding A&R risk appetite in 1993.

Neil’s Facts about Undertow by Tool

| # | Fact | Talking Point |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Release date: 6 April 1993 | Tool’s full-length debut on Zoo Entertainment, distributed by BMG. |

| 2 | Producer: Sylvia Massy with Tool | Recorded at Grandmaster Recorders, Hollywood; mixed by Ron St. Germain. |

| 3 | Running time: ~69 minutes | The CD runs long because Disgustipated is indexed after Flood. |

| 4 | Line-up: Maynard James Keenan (vocals), Adam Jones (guitar), Danny Carey (drums), Paul D’Amour (bass) | The only Tool album featuring D’Amour before Justin Chancellor joined. |

| 5 | Guest cameo: Henry Rollins on Bottom | He delivers a spoken interlude mid-song — not a duet, more a psychological break. |

| 6 | Signature sound: Drop-D tuning, dry mix, huge dynamics | Tool’s restraint and rhythmic precision set them apart from LA’s funk-metal crowd. |

| 7 | Sober | Broke the band via MTV; its eerie stop-motion video was co-created by guitarist Adam Jones. |

| 8 | Prison Sex | Second single; partially banned on MTV for its disturbing imagery and subject matter. |

| 9 | Weird studio moment: Disgustipated features a destroyed piano | Sylvia Massy recorded the sound of it being hit with sledgehammers — Chris Haskett from Rollins Band helped. |

| 10 | Visual art: Ribcage cover by Adam Jones | Some US stores objected — censored versions replaced the cover with plain artwork. |

| 11 | Tour breakthrough: Lollapalooza 1993, second stage | Crowds grew so large Tool were nearly bumped to the main stage mid-tour. |

| 12 | Sales: Multi-platinum in the US (RIAA) | A slow-burn success that kept selling for years rather than spiking on release. |

| 13 | Tone: Trauma, control, personal reckoning | Keenan’s vocals stay close-miked and unvarnished — no rock-god gloss. |

| 14 | Legacy: Blueprint for ’90s alt-metal discipline | Heavy without flash; cerebral without prog excess — paved the way for Ænima. |

| 15 | Context: Released the same year as Chaos A.D., Siamese Dream, and In Utero | 1993 was stacked — Undertow stood out for its severity and precision. |