Setting the Scene: Why Soulfly’s Self‑Titled Debut Mattered in 1998

By early 1998 the commercial centre of heavy music had shifted decisively towards rhythm‑first, down‑tuned guitar music with overt hip‑hop and alternative crossovers. The mid‑1990s had already put Korn, Deftones and Coal Chamber on MTV; in 1998, the lane widened. Label systems and touring platforms had adapted: Roadrunner Records was aggressively backing hybridised heavy bands (Fear Factory, Machine Head, later Slipknot), while festivals and package tours – not least Ozzfest, launched in 1996 – were built to showcase this new energy to tens of thousands each summer. The broader history shows how Ozzfest became the premier North American travelling festival for metal after 1996, accelerating the mainstreaming of nu‑metal and allied styles (LiveAbout: Heavy metal timeline). Against this backdrop, the arrival of a new band led by Max Cavalera had an inbuilt audience.

We recorded a killer podcast about Soulfly here:

Cavalera’s profile before 1998 mattered. With Sepultura, he had helped push extreme and groove metal towards mainstream notice. Chaos A.D. (1993) and Roots (1996) melded bounce‑laden riffing with Brazilian percussion and collaborations with hip‑hop/alternative figures. Both were U.S. Gold albums and internationally charting titles (Blabbermouth: Paulo Xisto interview). Roots in particular foregrounded indigenous Brazilian elements and polyrhythms in a way that changed how “heavy” could sound on a global stage. When Cavalera left Sepultura in late 1996 after internal and managerial disputes, there was immediate industry interest in what he would do next; both press and fans expected a rhythmic, collaborative, globally aware project rather than a straight replication of past work.

The appetite for rhythm‑forward, hybridised metal in 1998 had distinct components:

- Downtuning and groove: seven‑string and dropped tunings (Korn) and bounce‑driven drumming emphasised head‑nod feel over speed.

- Hip‑hop and DJ elements: turntables and rap verses had become routine in heavy contexts (e.g., Limp Bizkit’s mainstream surge through 1997–1999).

- Non‑Western percussion: post‑Roots, Brazilian and Latin rhythmic colours were a recognised, audience‑tested part of heavy music’s palette.

Concrete 1998 examples underscore this climate: System of a Down’s debut (30 June 1998) fused Armenian melodies and alt‑metal; Fear Factory’s Obsolete (28 July 1998) took industrial-groove to a U.S. chart peak for the band; Korn’s Follow the Leader (18 August 1998) exploded commercially with a multi‑platinum run and MTV dominance. These releases shaped expectations about what a 1998 heavy record could do with rhythm, texture, and collaboration (Wikipedia: System of a Down (1998); Wikipedia: Fear Factory – Obsolete; Riffology: Korn – Follow the Leader).

Pre‑release media around Soulfly leaned into the idea of a “tribal” groove metal statement with guests. Cavalera was explicit that he did not want to remake Sepultura but to build something spiritually framed and collaborative. Contemporary coverage (summarised in later retrospectives) has him stressing that Soulfly would braid heavy rhythms with hip‑hop and world instrumentation and that the name itself signified a spiritual concept rather than a stylistic pigeonhole (Wikipedia: Soulfly (album)). The sense from Roadrunner’s positioning and press questions was that the record would be a test of whether post‑Sepultura Cavalera could channel grief, community and rhythmic heft into a new banner.

At a glance, the album arrived with clear markers of intent:

- Release date: 21 April 1998 (worldwide; Japan 24 February 1998)

- Label: Roadrunner Records

- Production: Ross Robinson (principal), with Andy Wallace mixing and George Marino mastering

- Core line‑up: Max Cavalera (vocals, rhythm guitar, percussion), Jackson Bandeira (guitar), Marcelo Dias (bass), Roy Mayorga (drums)

- Guests promised: figures from Fear Factory, Limp Bizkit, Deftones, Dub War/Skindred, Cypress Hill, and Brazilian percussionists from the Chico Science & Nação Zumbi circle (AllMusic: Soulfly; Discogs: Soulfly – master release).

This article takes an evidence‑led route through the formation, recording, sound, tracks, reception and legacy of Soulfly’s debut – with 1998’s broader heavy climate as context and with concrete data on charts, sales and personnel. It also addresses where facts diverge across sources.

| Artist – Album | Release date (1998) | Peak charts (selected) | Notable stylistic traits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soulfly – Soulfly | 21 April | US #79; UK #16; France #14; Germany #29; Australia #33 | Groove/nu‑metal with Brazilian percussion, hip‑hop/DJ features, guest‑driven |

| Fear Factory – Obsolete | 28 July | US #77 (band’s then-best); UK #28 | Industrial groove, concept framing, cyber‑aesthetics |

| System of a Down – System of a Down | 30 June | US #124; UK #13 (re‑entries later) | Alt‑metal with Middle‑Eastern motifs and vocal theatrics |

| Korn – Follow the Leader | 18 August | US #1; UK #4; multi‑platinum | Downtuned bounce, high‑profile hip‑hop crossovers, MTV saturation |

Sources for table: Wikipedia: Soulfly (album); Wikipedia: Obsolete; Wikipedia: System of a Down (album); Riffology: Follow the Leader.

From Sepultura to Soulfly: Formation, Line‑up, Intent

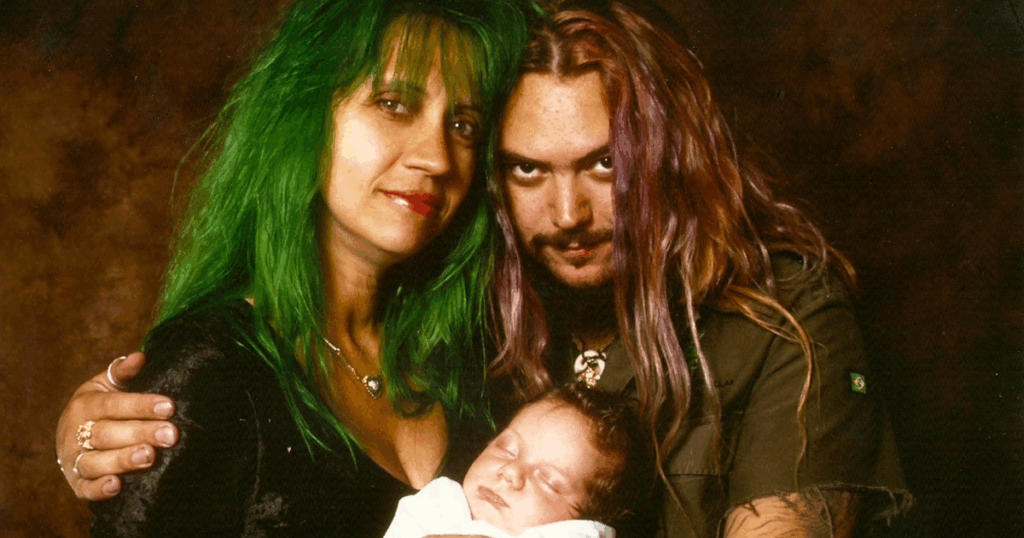

The chain of events from Cavalera’s last Sepultura show to Soulfly’s first recordings is crucial to understanding the project’s intent. Sepultura played Brixton Academy, London, on 16 December 1996, the final show of the Roots tour and Cavalera’s last with the band, days after internal conflict around management – especially the dismissal of Gloria Cavalera (Max’s wife) – split the group (Blabbermouth: Paulo Xisto interview). Within months, Max Cavalera began assembling a new unit in Phoenix, Arizona. He retained his core vision of heavy rhythm and social‑spiritual themes but wanted a fresh identity that explicitly avoided Sepultura replication. In interviews quoted in later sources, he cast Soulfly as a new “tribal” groove and spiritual project with open doors to guests and non‑metal instruments (Wikipedia: Soulfly (album)).

The initial line‑up set the musical direction:

- Max Cavalera – vocals, rhythm guitar, creative director, primary songwriter

- Jackson Bandeira – guitars (the credits list Lúcio Maia on certain parts, but Bandeira is the touring/early‑era guitarist of record)

- Marcelo Dias – bass (also credited as Marcello D. Rapp in some sources)

- Roy “Rata” Mayorga – drums and percussion

All four had complementary skill sets: Cavalera brought concept, riffs and a lifetime of Brazilian rhythmic vocabulary; Mayorga (ex‑Nausea) could bridge hardcore bluntness with polyrhythmic colour; Dias added both electric and acoustic/double bass; Bandeira filled out the mid‑gain rhythmic wall. In interviews across the period, Cavalera emphasised the “tribal” percussion and a desire to have different line‑ups and collaborators album‑to‑album to keep the project evolving (AllMusic: Soulfly).

Name and intent were bound together. The moniker “Soulfly” – variously connected by Cavalera to spiritual notions and to his involvement with Deftones’ “Headup” in 1997 – was designed to signal something broader than a “band” in the traditional sense: a vehicle for heavy grooves, global percussion and community‑minded themes. The philosophical framework, as reported later, included dedications to the memory of Cavalera’s stepson Dana Wells, who had died in 1996; grief and commemoration run through several early Soulfly songs and instrumentals in a consciously non‑nihilistic way (Metal Wiki: Max Cavalera).

Early momentum came from rehearsals that doubled as proof‑of‑concept for Roadrunner. The label’s late‑1990s strategy was to sign and platform rhythmically modern, crossover‑friendly heavy acts while leveraging producers with a sonic fingerprint. Ross Robinson – who had produced Sepultura’s Roots and pivotal late‑90s heavy albums – was the obvious choice for a first album designed to foreground immediacy and percussive shock. Robinson’s Malibu base, Indigo Ranch, had become a hub for capturing urgent, raw performances and a distinctive live‑room drum sound (Wikipedia: Soulfly (album)). Roadrunner’s marketing leaned into both Cavalera’s stature and the album’s guest cast; contemporaneous press framed Soulfly as a bold continuation rather than a nostalgia project.

Cavalera’s personal transition shaped the direction. The death of Dana Wells in 1996 had already imprinted itself on the closing phase of Sepultura and on Cavalera’s collaboration with Deftones (“Headup”). Soulfly’s debut institutionalised memorial, community and healing as recurring ideas, from the choice of collaborators (family voices appear in the credits) to the inclusion of instrumentals under the name “Soulfly” that served as breathers and meditations within the otherwise aggressive running order. Interviews from the era often paraphrased Cavalera as seeking to turn loss into a communal ritual of sound and rhythm (Metal Wiki: Max Cavalera).

Pre‑release buzz built around two poles: the promise of features from figures like Burton C. Bell and Dino Cazares (Fear Factory), Fred Durst and DJ Lethal (Limp Bizkit), and Chino Moreno (Deftones); and the expectation of Brazilian percussion heavy in the mix, with members of the Chico Science & Nação Zumbi circle (Gilmar Bola Oito, Jorge Du Peixe) participating. Roadrunner trailed “Eye for an Eye” and “Bleed” to rock radio and press, the former as a manifesto of Cavalera’s renewed heaviness and the latter as the crossover‑explicit collaboration. By the time Soulfly hit shops in April 1998, there was clarity: this was a fresh chapter, spiritually explicit and rhythm‑centred, with Cavalera curating rather than simply fronting a four‑piece (Wikipedia: Soulfly (album)).

Writing and Recording: Studios, Personnel, Production Choices

Recording took place at Indigo Ranch Studios, Malibu, California, across 1997–1998 with Ross Robinson producing and Richard Kaplan engineering. Indigo Ranch’s live room and Robinson’s tracking ethos (band in a room; bleed embraced; performances prioritised over micro‑editing) were perfect for Soulfly’s percussive intent. In 1998 heavy music, Robinson’s work was a marker of intensity – he had been central to Korn, Deftones and Sepultura sessions – while Andy Wallace’s mixes were known for muscular low‑end and articulate drum/guitar separation, and George Marino’s mastering gave commercial bite (Wikipedia: Soulfly (album)). The sonic chain matters because the record lives and dies on kick/snare impact and mid‑range guitar chest‑punch; this team delivered that.

Principal personnel included the core band and an unusually broad guest roster:

- Fear Factory’s Dino Cazares (guitar) and Burton C. Bell (vocals) on “Eye for an Eye”

- Fred Durst (vocals) and DJ Lethal (turntables) on “Bleed”; DJ Lethal also on “Quilombo”

- Chino Moreno (vocals) on “First Commandment”

- Benji Webbe (vocals; Dub War/Skindred) on “Quilombo” and “Prejudice”

- Eric Bobo (Cypress Hill) and Brazilian percussionists Gilmar Bola Oito and Jorge Du Peixe (Chico Science & Nação Zumbi) on various tracks

- Christian Olde Wolbers (double bass) on “No”

Writing evolved from riff‑first sketches into drum‑and‑percussion frameworks. Cavalera has long developed riffs with four‑string rhythm guitar setups, focusing on percussive down‑picking and open‑string drones rather than elaborate harmony. Pre‑production reportedly foregrounded groove tests – tempos in the mid‑90s to 120 bpm were common – and layerable percussion motifs. Samples and DJ elements were integrated as “instruments” rather than decorative add‑ons, with turntables used rhythmically alongside floor toms and afrobrazilian drums. Mario Caldato Jr. co‑produced the Brazilian‑leaning “Bumba” and “Umbabarauma,” underscoring the album’s open architecture (Wikipedia: Soulfly (album)).

Production aesthetics reflect late‑1990s heaviness but with distinct choices:

- Guitars: aggressively mid‑forward, with saturation that keeps pick attack audible. Exact tunings are variously reported in fan/tech forums (commonly drop‑C family), but reliable primary documentation is scarce; what is clear is the downtuning and the choice to prioritise punch over scooped sheen. Where tunings are disputed, this article does not assert specifics beyond “downtuned” (contested fact).

- Drums: Indigo Ranch’s live room helped deliver a hard, woody snare and weighty toms. Mayorga’s parts are tracked for feel rather than grid precision, with flams and fills recorded as performance events rather than edited.

- Bass: thick and present, sometimes doubling guitar riffs, sometimes moving independently for “heft.” Notably, Dias provides acoustic and double bass on the instrumental “Soulfly” and the deep resonance in “No.”

- Vocals: Cavalera’s lead is captured hot, with limited polish, retaining grit and breath; guest vocals are mixed in as discrete character layers rather than background adornment.

- Mastering: George Marino’s cut adds competitive loudness for 1998 but preserves transient clarity by the standards of the time.

Non‑Western instruments are integral: berimbau frames key moments; alfaia bass drums, triangle, chocalho and other Carnival/maracatu instruments deepen the low‑mid rhythmic bed. These are recorded close‑miked and as room layers, giving “Bumba,” “Umbabarauma” and “Tribe” their particular movement. Field elements are minimal; this is studio‑constructed, not documentary, but the massed‑voice chant sections and gang vocals mimic street‑ensemble feel. Liner‑note‑level credits confirm instrument and percussion roles track‑by‑track (Discogs: Soulfly – master).

| Studio/credit | Details |

|---|---|

| Recording studio | Indigo Ranch Studios, Malibu, California (1997–1998 sessions) |

| Producer | Ross Robinson (Mario Caldato Jr. co‑producer on “Bumba” and “Umbabarauma”) |

| Engineering | Richard Kaplan; additional engineering by Chuck Johnson, Rob Agnello |

| Mixing | Andy Wallace (principal); select additional credits per track |

| Mastering | George Marino |

| Notable outboard/console | Indigo Ranch’s analogue-forward chain; Robinson-era sessions typically used high-SPL drum capture and minimal gating (period practice; specific console not itemised in primary sources) |

Legal/clearance notes centre on clearly credited covers and interpolations: “Umbabarauma” is a Jorge Ben Jor composition; the Discharge covers added to limited editions are writer‑credited; “The Song Remains Insane” incorporates “Caos” (Ratos de Porão) and an aggressively re‑imagined “Attitude” (Sepultura), credited accordingly in sources aggregating liner details (Wikipedia: Soulfly (album)).

Sound, Style, and Themes: Groove, Crossover, World Influences

Sonically, Soulfly’s debut balances three pillars: groove‑metal riffing, hip‑hop/DJ integrations and Brazilian percussion working as a co‑equal rhythmic engine. Tempos span roughly mid‑90s to 130 bpm, with an emphasis on back‑beat snap and open‑string chug. “Eye for an Eye” sets the template: a short, barreling 3:35 built on downtuned, palm‑muted riffs and a hammered snare‑on‑two‑and‑four. Fear Factory’s Dino Cazares adds his precise down‑picking attack, while Burton C. Bell’s backing voice colours the final drive (Wikipedia). “Bleed” shows the hip‑hop element in full relief: DJ Lethal’s scratches work rhythmically with toms; Fred Durst’s guest verse slots into the bar structure as a percussive contour rather than a genre detour. “Tribe” and “Bumba” demonstrate the album’s polyrhythmic ambitions, with alfaia drums, shakers and hand percussion creating interlocking patterns under/around the kit and guitars.

Stylistic influences are traceable:

- Thrash/groove roots: Cavalera’s riff sense bears the imprint of late 1980s Sepultura but slowed and simplified into bounce‑friendly figures.

- Nu‑metal contemporaries: the turntable usage and guest vocal curation place the album in the same ecosystem as Korn and Limp Bizkit, while the production team (Robinson/Wallace) situates it inside late‑90s mainstream heavy sonics.

- Hip‑hop elements: scratches and programmed flavouring augment – not replace – live percussion; vocals are often gang‑style or call‑and‑response, with chant‑like cadences.

- Brazilian/Latin and global rhythms: the alfaia and maracatu vocabulary, berimbau ostinati, and samba‑adjacent shakers extend beyond “colour” into structure, especially on “Bumba,” “Umbabarauma,” and “Tribe.”

Themes cohere around community, spirituality, loss and resilience. Contemporary and retrospective sources consistently report that Cavalera viewed Soulfly as a spiritually inflected project, with album dedications and track titles signalling remembrance and uplift without sentimentality. “Soulfly,” the instrumental, works as a reflective interlude with acoustic bass, sitar and percussion; “First Commandment” nods to moral/ethical framing while “Prejudice” is a blunt rejection of division. Grief over Dana Wells is one of the album’s unspoken drivers; pieces like “Bleed” and the closing atmosphere of “Karmageddon” turn that grief into forward motion rather than stasis (Metal Wiki: Max Cavalera).

Guests expand the palette materially. Two illustrative cases:

- Fred Durst and DJ Lethal on “Bleed”: away from Limp Bizkit’s own albums, their presence here functions as a groove enhancer and momentum shift, with scratches operating like an extra hi‑hat layer and Durst trading lines against Cavalera’s gutturals. The result reads as “metal with hip‑hop musculature,” not a rap‑metal bolt‑on (Wikipedia: track personnel).

- Benji Webbe on “Quilombo” and “Prejudice”: coming from Dub War’s ragga‑metal lineage and later Skindred, Webbe’s cadence and chains‑on‑metal textures create a heavy ragga undertow, demonstrating how Caribbean rhythmic phrasing can ride a Brazilian‑inflected groove bed. This is 1998’s crossover writ large: not genre compromise but rhythm‑system fusion.

Compared with near‑time peers on Roadrunner and Robinson‑associated projects, Soulfly is less claustrophobic than, say, Korn’s 1998 work and more overtly percussive than the industrial‑tight grind of Fear Factory. The Wallace‑Marino finishing chain yields a clear, loud record by period standards without fully crushing the drum transients, especially in Brazilian percussion passages (AllMusic). Where specific technical facts (e.g., exact tunings) are contested in fan circles, the most reliable description remains: downtuned, percussive, mid‑forward guitars; hard, dry snare; integrated non‑kit percussion; voice‑as‑rhythm throughout.

For fans of (mapping by musical features):

- Sepultura – Roots‑era polyrhythm and groove (Riffology: The Making of Roots)

- Dub War/Skindred – ragga‑metal vocal phrasing and bounce

- Deftones – percussive guitar phrasing and collaborative spirit (Riffology: Deftones – Adrenaline)

- Limp Bizkit – hip‑hop turntablism integrated with metal riffing

Track‑by‑Track Highlights and Musical Analysis

Track list (standard edition; timings per reliable discographic sources):

- 1. Eye for an Eye – 3:35 (feat. Dino Cazares, Burton C. Bell)

- 2. No Hope = No Fear – 4:36

- 3. Bleed – 4:07 (feat. Fred Durst, DJ Lethal)

- 4. Tribe – 6:02

- 5. Bumba – 3:59 (feat. Los Hooligans)

- 6. First Commandment – 4:29 (feat. Chino Moreno)

- 7. Bumbklaatt – 3:52

- 8. Soulfly – 4:49 (instrumental)

- 9. Umbabarauma – 4:11 (Jorge Ben Jor cover; feat. Los Hooligans)

- 10. Quilombo – 3:44 (feat. Benji Webbe, DJ Lethal)

- 11. Fire – 4:21

- 12. The Song Remains Insane – 3:40 (integrates “Caos” and “Attitude” reinterpretation)

- 13. No – 4:00 (feat. Christian Olde Wolbers on double bass)

- 14. Prejudice – 6:52 (feat. Benji Webbe)

- 15. Karmageddon – 5:44 (contains hidden “Sultão das Matas”)

Selected regional bonus tracks include Discharge covers (“Ain’t No Feeble Bastard,” “The Possibility of Life’s Destruction”) and “Cangaceiro” (limited/digipak editions), plus a Roadrunner 25th anniversary reissue adding the studio track “Blow Away” and a 1998 Roskilde Festival live set (Wikipedia: Soulfly (album)).

Key track analyses:

Eye for an Eye: A compact thesis statement. The main riff is an alternation between a low‑string, palm‑muted pedal and a two‑note, percussive movement that locks to Mayorga’s kick. The arrangement is minimal – two core riffs, a mid‑section accent, and a final build – which keeps the focus on vocal cadence and drum/guitar synchrony. Dino Cazares’s rhythm guitar tightens the pick attack, and Burton C. Bell’s backing lines add edge without dominating. The mix keeps the snare dry and the guitars forward; it’s a reference‑point opener for the album’s tone (AllMusic).

Bleed: Opens with a rhythmic motif that foregrounds toms and scratches in unison. The main guitar figure uses open‑string chug with syncopated rests; turntables fill those spaces. Fred Durst’s entrance shifts the cadence, trading phrases with Cavalera. The chorus cadence is chant‑like, but the hook is ultimately rhythmic (snare and scratch). Production‑wise, this is the record’s clearest hip‑hop/metal co‑weave, emblematic of 1998’s crossover logic. Contemporary coverage often referenced the personal impetus behind the song’s intensity (Metal Wiki: Max Cavalera).

Tribe: The longest fully heavy cut (6:02) uses layered percussion to create forward momentum without upping tempo. The berimbau motif returns as a leitmotif, while alfaia‑style low drums thicken the groove below kit level. The mid‑section opens space for gang vocals and percussion call‑and‑response. Structurally, the song alternates between anchored chug sections and more open, chant‑driven passages, reflecting the “tribe” idea in arrangement. The breakdown riff reportedly has roots in Cavalera’s late Sepultura sketchbook, but here it is embedded in a new rhythmic environment (Wikipedia).

First Commandment: Featuring Chino Moreno, it moves between heavier verses and a more spacious refrain where Moreno’s timbre contrasts Cavalera’s bark. Instrumentally, a sitar layer adds an otherworldly sheen; this is one of the clearest examples of Soulfly using non‑Western timbre to alter a song’s emotional contour rather than for ornament. The dynamic play – heavy verse, airier refrain – is a Robinson‑era hallmark.

Umbabarauma: Jorge Ben Jor’s 1976 song is recontextualised with thick guitars and Carnival‑grounded percussion. Los Hooligans’ presence and Mario Caldato Jr.’s co‑production emphasise an authentic swing beneath the metal shell. The kit plays straighter, while percussion pushes a dancing trip‑feel; the result is a celebratory centrepiece where metal heft is secondary to groove.

Quilombo: Benji Webbe’s vocal phrasing and DJ Lethal’s turntablism push this towards ragga‑metal. Chains and found‑metal textures serve as percussion. The guitar riffing is repetitive by design – a mantra for the vocal and percussion exchanges. It demonstrates Soulfly’s willingness to make voice and percussion the lead instruments while guitars become a pulse bed.

The Song Remains Insane: A kinetic medley/pastiche that folds hardcore velocity into Soulfly’s groove architecture, interlacing Ratos de Porão’s “Caos” elements and a spike of Sepultura’s “Attitude” re‑imagined. It is the album’s fastest feel in parts, showing Cavalera still happy to hit punk speeds when the arrangement demands it (Wikipedia).

No: The double bass (Christian Olde Wolbers) gives the low end an organic, woody resonance, contrasting the compressed heaviness elsewhere. The song uses stop‑start riff figures with emphatic rests, leaning into the record’s tight/loose tension – a clear Wallace mix decision to leave space around the transients.

Prejudice: At 6:52, it is one of the set’s longest immersion pieces. Benji Webbe’s presence and chain‑percussion textures turn the groove into a rolling, insistent cadence. There is a deliberate stacking of percussive elements across the runtime so that the last third feels thick without being faster. The message is built into arrangement and chant logic rather than melodic hook.

“Soulfly” (instrumental): The album’s reflective core. Acoustic bass, sitar and hand percussion create a meditative aura with modal flavour. In sequencing terms, it resets the ear mid‑album and underlines the project’s spiritual framing.

Singles and videos: “Eye for an Eye” (single 23 February 1998), “Umbabarauma” (5 May 1998), “Bleed” (23 December 1998), and “Tribe” (21 January 1999) were rolled out across the campaign (Wikipedia: singles). Official uploads and network rotations supported awareness through 1998–1999.

| Track | Confirmed guests | Key instruments/elements | Production notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eye for an Eye | Dino Cazares (guitar), Burton C. Bell (backing vox) | Downtuned rhythm wall; dry snare | Robinson/WALLACE/Marino core chain |

| Bleed | Fred Durst (vox), DJ Lethal (turntables) | Scratches doubling toms; chant cadences | Hip‑hop/metal blend captured live‑room style |

| Tribe | — | Berimbau, alfaia, layered shakers | Percussion up in the mix; extended runtime |

| First Commandment | Chino Moreno (vox) | Sitar atmospherics | Dynamic contrast around guest timbre |

| Umbabarauma | Los Hooligans; percussionists | Carnival drums, chocalho | Co‑prod. by Mario Caldato Jr. |

| Quilombo | Benji Webbe (vox), DJ Lethal | Ragga cadence; chains; turntables | Voice/percussion foregrounded |

| No | Christian Olde Wolbers (double bass) | Acoustic low‑end body | Mix leaves headroom for resonance |

| Prejudice | Benji Webbe (vox) | Chains, layered gang vox | Long‑form percussive build |

Sources: Wikipedia: track credits; Discogs master.

Live staples: setlist aggregations show “Eye for an Eye,” “Bleed,” “Tribe” and “Bumbklaatt” recurring across 1998–1999, with Roskilde 1998 documented on the Roadrunner 25th anniversary reissue’s bonus disc (Wikipedia: reissue contents; setlist.fm for tour‑era set patterns).

Release Strategy, Artwork, Formats, and Packaging

Release was staggered: Japan on 24 February 1998, then worldwide on 21 April 1998 via Roadrunner Records (Wikipedia). Roadrunner’s global infrastructure – with strong European distribution – helped the album chart widely in its opening weeks. The label supported with singles staged across the year, a touring push into European festivals (notably Roskilde 1998) and video/radio servicing of “Eye for an Eye,” “Bleed,” “Umbabarauma” and “Tribe.”

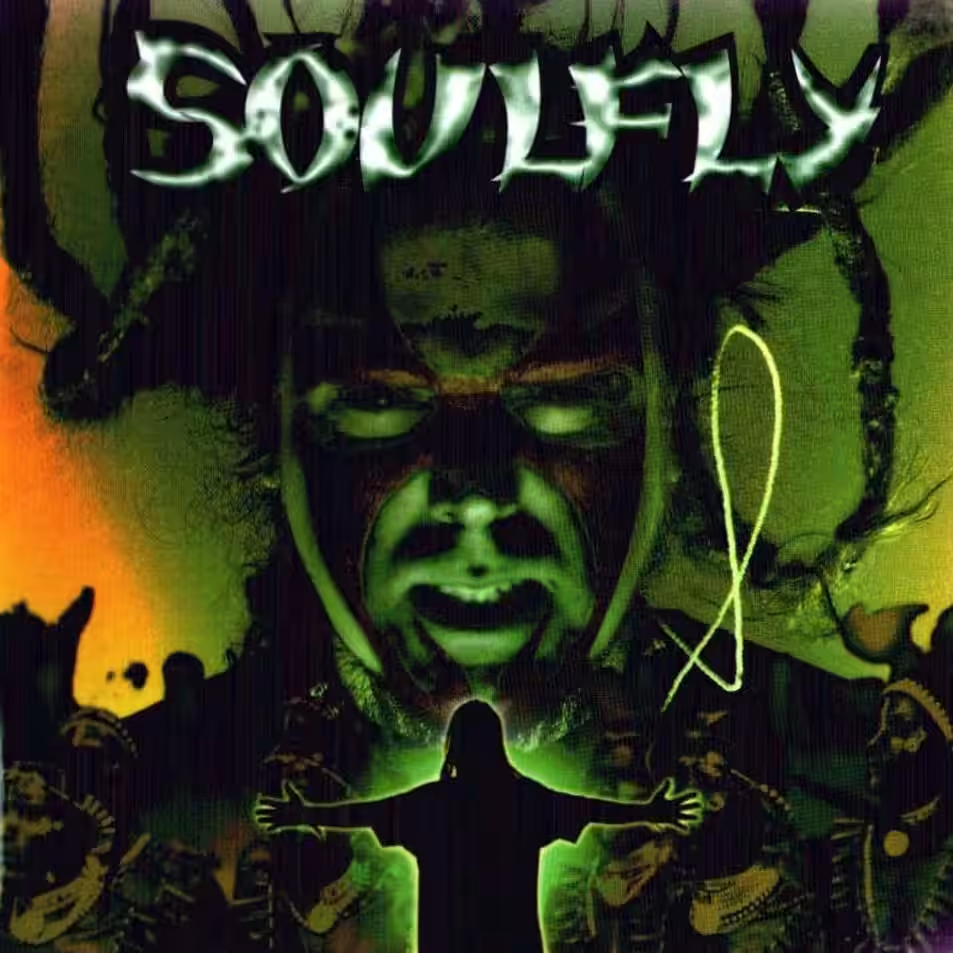

Artwork and design: the cover photo credit goes to Jo Kirchherr; art direction and design were handled by Pawn Shop Press, with supporting photography by Glen LaFerman and Christy Priske (Wikipedia). The visual language – earthy green/brown palette, symbolic logotypes – aligned with the “tribal”/spiritual framing while keeping the band identity front‑and‑centre. In marketing collateral, the cover’s strong logotype and colour scheme gave Roadrunner a recognisable motif for posters and print adverts.

Formats and editions:

- Standard CD (worldwide), jewel case

- Japanese CD (bonus tracks including “Cangaceiro” and Discharge covers)

- European limited digipak with a bonus disc of remixes and live tracks (e.g., live “No Hope = No Fear,” “Bleed”)

- Cassette editions in select territories

- Roadrunner 25th Anniversary reissue (2×CD): original album + 1998 Roskilde Festival live set and additional archival audio

Discogs aggregates a wide array of pressings and packaging variants, including regional barcodes and matrix/runout identifiers (Discogs master). Catalogue numbers vary by territory and edition; collectors should reference Discogs per pressing to avoid confusion.

Promotional strategy combined radio adds at active rock/metal, print features leveraging Cavalera’s profile, and high‑visibility festival dates. The singles rollout bridged both the album’s heaviness (“Eye for an Eye,” “Tribe”) and its crossover (“Bleed,” “Umbabarauma”), giving programmers multiple on‑ramps. A steady trickle of remixes/live tracks on limited editions fuelled fan engagement in 1998–1999.

| Edition | Region | Format | Distinguishing features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard album | US/EU | CD/cassette | 15 tracks, standard booklet with full credits |

| Japanese CD | Japan | CD | Adds “Cangaceiro,” Discharge covers; Japanese liner notes/obi |

| EU digipak (limited) | Europe | CD + bonus CD | Remixes and live tracks; fold‑out packaging |

| Roadrunner 25th Anniversary reissue | Various | 2×CD | Adds Roskilde 1998 live set and “Blow Away” |

Source: Discogs: Soulfly – master release; Wikipedia.

Reception, Charts, Sales, and Touring Cycle

Contemporary critical reception framed Soulfly as both a strong first statement and an album whose breadth was part of its identity. AllMusic emphasised the fusion of Brazilian tribal rhythms with heavy metal riffing as a defining quality (AllMusic). Round‑ups compiled on the album’s page show mainstream rock press grading in the positive-to‑mixed‑positive range (e.g., NME ~7/10; Hit Parader “B”), with praise focusing on groove/impact and guest chemistry, and typical reservations centring on stylistic sprawl (Wikipedia: review summary).

Chart performance was broad for a debut from a new name. Verified peaks include: U.S. Billboard 200 #79; U.K. Albums Chart #16; France #14; Germany #29; Australia #33; Belgium (Flanders) #12; Netherlands #27; Finland #18; New Zealand #14; Sweden #43, among others (Wikipedia: chart table; Official Charts Company; Billboard 200). The album achieved RIAA Gold certification in the United States (500,000 units) and ARIA Gold in Australia (35,000 units at the time), confirming substantial cumulative sales (RIAA Gold & Platinum; Wikipedia: certifications). Precise first‑week U.S. sales are not reliably published in the accessible sources; what is certain is the cumulative certification threshold met thereafter.

Singles nurtured visibility across 1998–1999. “Eye for an Eye” (February 1998) functioned as the heavy lead; “Umbabarauma” (May) signalled the album’s global palette; “Bleed” (December) and “Tribe” (January 1999) extended rotation into the following year (Wikipedia: singles). In the U.K., the album’s #16 peak reflected strong early uptake – a notable achievement for a new banner without the Sepultura name (Official Charts Company).

Touring 1998–1999 concentrated on club headliners, European festivals and U.S. support slots. A keystone was Roskilde Festival 1998, documented on the Roadrunner 25th Anniversary reissue with a 14‑track live set – direct evidence of the band’s positioning on major European stages within months of release (Wikipedia: reissue contents). Press and setlist archives indicate “Eye for an Eye,” “Bleed,” “Tribe” and “Bumbklaatt” as anchors, with Cavalera occasionally including Sepultura classics in medleys to serve audience demand (setlist.fm).

No significant controversies specific to the album campaign are reported in the sources consulted; the narrative arc remained focused on the music, the guest‑driven collaboration and Cavalera’s post‑Sepultura reset.

| Country | Peak chart | Certification |

|---|---|---|

| United States | #79 (Billboard 200) | RIAA Gold |

| United Kingdom | #16 (OCC) | — |

| France | #14 | — |

| Germany | #29 | — |

| Australia | #33 | ARIA Gold |

| Belgium (Flanders) | #12 | — |

| Netherlands | #27 | — |

| Finland | #18 | — |

| New Zealand | #14 | — |

Source: Wikipedia: chart/certification table; RIAA.

Facts About the Record

- Release dates: 21 April 1998 worldwide; 24 February 1998 Japan (Roadrunner).

- Label: Roadrunner Records, then at the peak of its nu-metal crossover push.

- Studio & team: Recorded 1997–1998 at Indigo Ranch, Malibu. Produced by Ross Robinson (Sepultura, Korn), mixed by Andy Wallace (Nirvana, Rage Against the Machine), mastered by George Marino (Metallica, AC/DC).

- Core band: Max Cavalera (vocals, rhythm guitar, berimbau, sitar, talk box), Jackson Bandeira (guitar), Marcelo Dias (bass, acoustic/double bass), Roy Mayorga (drums/percussion).

- Guest roster (at least nine named): Dino Cazares & Burton C. Bell (Fear Factory), Fred Durst & DJ Lethal (Limp Bizkit), Chino Moreno (Deftones), Benji Webbe (Dub War/Skindred), Eric Bobo (Cypress Hill), Christian Olde Wolbers (double bass), plus Brazilian percussionists Gilmar Bola Oito and Jorge Du Peixe (Chico Science & Nação Zumbi).

- Runtime: 68:03 (standard edition).

- Charts & certifications: US Billboard 200 #79, UK #16 (highest Soulfly UK peak until 2002), France #14, Germany #29, Australia #33. Certified Gold in the US (500k+) and Australia (35k+).

- Singles: Four between Feb 1998–Jan 1999 – Eye for an Eye, Umbabarauma, Bleed, Tribe.

- Touring: Major European festivals within months; Roskilde 1998 performance captured and later released in full on Roadrunner’s 25th Anniversary reissue.

- Artwork: Cover photo by Jo Kirchherr; earthy palette and tribal motifs designed by Pawn Shop Press to reflect the album’s “spiritual groove” ethos.

- Equipment & sound:

- Cavalera often tracked on a stripped-down four-string guitar for percussive down-picking.

- Downtuned, mid-forward guitar tone designed for punch, not gloss.

- Brazilian percussion (berimbau, alfaia, chocalho, triangle) integrated with kit; chains and found-metal used as textures.

- Robinson’s performance-first ethos preserved bleed; Wallace mixes gave clarity to low-end; Marino mastering delivered 1998-era loudness while keeping drum/guitar transients intact.

Did You Know?

- The Song Remains Insane embeds Ratos de Porão’s “Caos” and a re-arranged nod to Sepultura’s “Attitude” – Cavalera acknowledging his past while reframing it.

- Japanese & EU limited editions added Discharge covers (Ain’t No Feeble Bastard, The Possibility of Life’s Destruction), showing Cavalera’s hardcore roots alongside the tribal/hip-hop palette.

- Mario Caldato Jr. (Beastie Boys engineer/producer) co-produced Bumba and Umbabarauma, cementing Soulfly’s hip-hop/Brazilian crossover DNA.

- Roskilde 1998 setlists show Soulfly mixing new material with Sepultura classics – easing Cavalera’s transition for fans.

- The hidden track “Sultão das Matas” at the end of Karmageddon is a nod to Brazilian folklore.

Closing Thoughts: Soulfly’s Debut in Retrospect

Soulfly’s self-titled debut stands as both a continuation and a rupture. It carried Max Cavalera’s rhythmic instincts, collaborative reach and political-spiritual framing into a new context, but it also marked a decisive break from the Sepultura name. In 1998, that distinction mattered: the heavy landscape was already shifting toward hybrid forms, and Soulfly provided one of its clearest articulations.

What gives the record longevity is less its sales figures or guest list than the way it codified a different logic of “heaviness.” Percussion and groove were not embellishments but foundations; grief and community sat alongside aggression; hip-hop and Brazilian voices were integrated as equals rather than curiosities. That blueprint would guide Cavalera across subsequent Soulfly records, but it is on the debut that the intent feels most urgent.

Revisiting it now underscores how transitional 1998 really was. Korn and Limp Bizkit were pushing the commercial envelope, System of a Down were just breaking through, and Fear Factory were at their conceptual peak. Into that mix came an album that insisted heavy music could be global, collaborative and spiritual without losing impact. The fact it charted across continents, went Gold in the U.S., and put Soulfly immediately on major festival stages shows how fully that proposition connected.

Two decades on, the debut remains the clearest statement of what Cavalera meant by “Soulfly” in the first place: music as rhythm, memory and ritual. It is less about polish than about presence, less about genre boundaries than about collapsing them. In that sense, Soulfly (1998) is not just a record of its moment but a reminder of how heavy music keeps renewing itself—by finding new ways to make rhythm, grief and community move as one.